We give ourselves away in words – avoiding ‘the ick’ in communications

“The ick” is a common phrase in our household. The almost fourteen-year-old uses it regularly: “Eww, that gives me the ick.” She utters these words variously, but always when her seven-year-old brother tries to be nice to her (usually somewhat suspicious). In the Netflix series “Nobody Wants This,” they dedicated a whole episode to the lead character (played by Kristen Bell) overcoming “the ick” of seeing her boyfriend suck up to her parents.

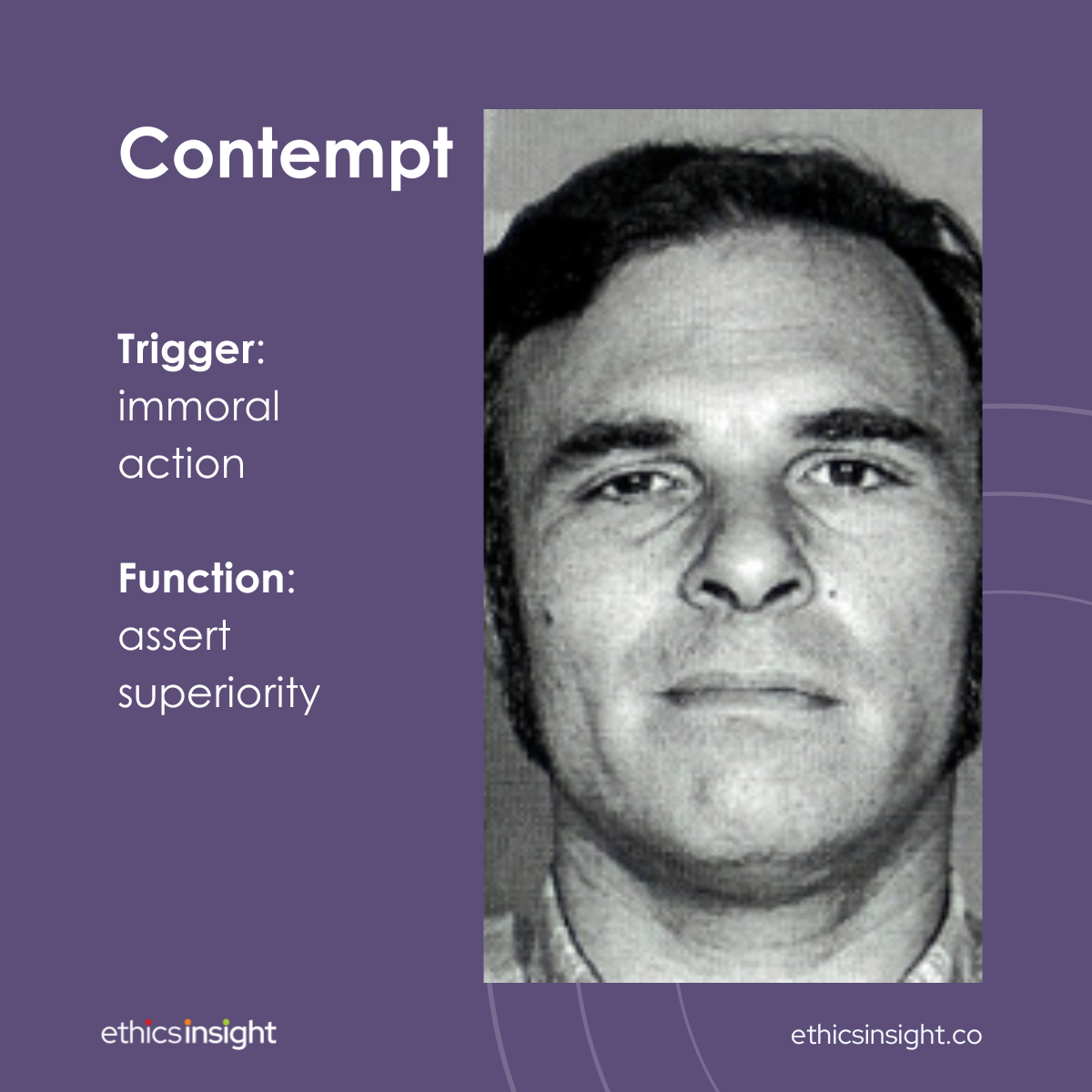

The episode discusses whether it’s possible to overcome the ick, that moment when someone repulses you or causes that contemptuous flicker. During studies in behavioural analysis, we were trained to spot visual clues, including micro-expressions (flickers lasting less than 0.25 seconds typically). I’ll pick one today: contempt. This expression is vital in what we do – building trust and environments where people can share. To explain why, Dr John Gottman’s research (popularised by the serial misrepresenter of data Malcolm Gladwell) showed that contempt is the number one predictor of divorce.

Conflict between couples was not the main predictor of failure. It’s the little things. Leaving toilet seats up, not stacking the dishwasher correctly, and not keeping to commitments that prompt flickers of contempt. Contempt is powerful. It’s defined (in behavioural science speak) as “an assertion of moral superiority.” If that feels unrelatable as a definition, try it. Raise one side of your mouth in a smirk and hold it. It makes you feel good.

Before training to spot these visual cues, the facilitators asked us to mirror and note the feelings. Micro-expressions and other fleeting emotional leaks (gestural, vocal turn, a slip of the tongue, etc.) are hard to recognise, even in yourself. Once you start to, you become more self-aware.

Reading a message from my daughter’s headteacher last week, I felt the flicker of contempt. Aly has been selected as a mentee by the headteacher. Good news, surely? Why, then, did I feel contempt? Here’s an extract from the email:

“…we believe we have a duty to ensure that all students are enabled and encouraged to make the most of their talents. Furthermore we understand that if our highest achieving students are nurtured and emboldened we create an environment in which learning is celebrated and rewarded which benefits our whole community. As such Alysia has been selected for our High Prior Attainers Plus (HPA+) programme. This will involve mentoring from myself to help guide Alysia through their time at Uckfield, making sure they maximise their potential. I will be meeting with Alysia shortly to decide what will help them the most and set some targets to help them achieve their best here. I’m really looking forward to working with Alysia over the next few years. We believe Alysia has great potential and you can be assured we will do our utmost to help them achieve.”

What do you see there that might annoy Aly’s parent?

A later stage in my behavioural science course involved linguistics, including statement analysis. A mini-analysis of that message might reveal:

💡 The saviour complex grandeur and tone from the amorphous we: “We have a duty,” “benefits our whole community”, in a school that fails in some of the basics (open debate, bullying, etc.).

💡 The overpromising juxtaposed with boilerplate anonymity, “making sure they maximise their potential [Aly is a she; this person does not know Aly].”

💡 The writer’s ego, “I will be meeting … to decide what will help them,” where any suggestion of Aly’s voice in this decision about her future is absent.

I asked Aly what this headteacher was like. She replied, “Her smile gives me the ick; it’s like her eyes are dead but piercing through you simultaneously.” I followed up by asking if she’d been consulted about whether or not she wanted the mentoring: “No, absolutely not. She’ll get me to do more of the ‘ambassador’ stuff teachers should be doing, and I’ll have even fewer friends.”

When those of us in risk and compliance roles communicate, we must consider these dynamics. We’re asking people (often) to go against their peers. Most working cultures I’ve been in are a 50/50 tightrope between those (relatively) content in their role and those actively seeking to leave or undermine “the management.” In this context, we can easily give people ‘the ick’ with a few misschosen words here or there. Not everyone will be as obsessive as I am and nitpick each line, but we might intuitively raise the corner of our mouths in contempt. At that point, the relationship is probably starting toward divorce. Many training and communication initiatives fail on these minutia.

Years ago, I arrived at work to find we’d each been left a flyer on our desk (a small card with the company’s rebranded values). My friend waited for me to read it and saw me scoffing. He had been an editor at a prominent London paper and said, “I couldn’t get past the first line.” The flyer started, “We value diversity in all its forms…” Diversity implies many forms; the final four words are not needed. For an editor, that is painful.

Communicating with an audience of critics and pedants like me and my former colleague is exhausting. But taking the time to reread our messages and consider ‘the ick’ can prevent the even greater exhaustion of contemptuous staff who actively resent us.