CEO Safety Crossover Compliance Lessons

Following the murder of Brian Thompson, the CEO of the American health insurance company UnitedHealthcare, a scurry of media reports that CEOs are beefing up their security. That alone will not help if facing a determined, resourceful, and asymmetrical threat.

In the mid-2000s, we got a call from an agitated security director. There’d been a terrible and tragic accident, claiming the lives of tens of people. The relatives of the deceased were understandably furious. Some demanded answers, others wanted blood. A few weeks later, we’d know the accident was caused by a negligent (and probably corrupt) government worker (a mandated supplier who introduced a combustible nightmare). But, at that moment, the relatives blamed the company, specifically the CEO and CFO.

The security director wanted what security directors often do: close protection for the two executives. But he also recognised a need to calibrate the threat (they’d had bomb threats, death notes, and extortion requests). My job was to do the risk assessment: a threat assessment (gathering intel on potential sources of threat) and a ‘red team’ vulnerability analysis (investigating the executives to identify weaknesses a threat actor could exploit).

Security is not just about security (physical, that is). It’s about predictability and resilience. During the red team analysis, we identified a plethora of data on the CEO (the CFO had led a more sheltered existence). In media interviews, he’d told us about his gym and club (Thursday evening ritual whisky), and we’d had photos inside his office (providing a mine of data including easy background landmarks enabling calibration of precise location). His daughter was less than discreet on Facebook, meaning that when paired with land registry records, we knew where he lived and when she’d be hosting an (easy to infiltrate) party. He even told us about his cycling route to work. There was more, but you get the idea. When we presented this data to the CEO, explaining that no close protection would keep a principle this predictable safe, his face dropped. Like Brian Thompson (interdicted at a predictable and publicised event), his predictability might have been his undoing.

We needed to move to resilience. What to do to respond to the threats. Contingencies. Plan B. Situational awareness. Hostile environment training (potentially, but not yet). Changing up routines, becoming less predictable. Making him a harder target would be easier than securing a sitting duck.

Back to compliance. We know many of the threats we face, at least in the abstract. Corrupt officials (maybe even calibrated down to particular departments and locations, e.g., Customs at Port Y). Fraudsters (outside the organisation). Suppliers and supply chain (👇) risks where we’re duped about inputs and origin. Threats within (disgruntled employees, insider trading, collusion, conflicts of interest, misappropriation, misuse of things including IP, etc.). Like the CEO, we live in a world of disclosure and openness. We don’t have the luxury of locking down what we do, when, and how so tightly that no one could exploit our predictability. Sometimes, our openness is mandated (e.g., disclosures, filing requirements, bid requirements, etc.).

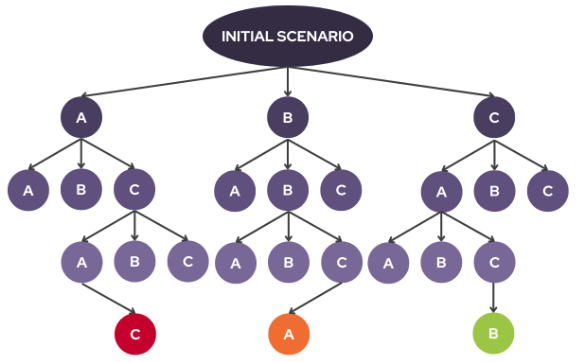

In this prism, might we focus less on security (throwing more bodies or, in compliance’s case, paper and forms at the problem)? Could we, instead, examine how our predictability could be exploited? If you’re wondering where to start in high-trust teams, you can ask people “How would you…” questions to have them play the ‘red team.’ If trust is unknown or lower, consider asking them about their past roles and lives: how things went wrong in ‘other’ places. That bit of distance opens avenues for discussing the past and the present (with a veneer of protection). Crisis simulations (where we assume something bad has already happened) can also be invaluable ways of opening up a world of data on actual risks and decision-making fallibility.

With a better understanding of where, when, and how we might get ‘hit,’ planning for resilience is much easier. Now, we can arm people with tools to spot issues likely to occur in their AOO (area of operation). Next, we must train them on resistance, avoidance, and mitigation. In my experience, organisations that do this well manage compliance more effectively and at a fraction of the cost of those who throw resources at the problem.